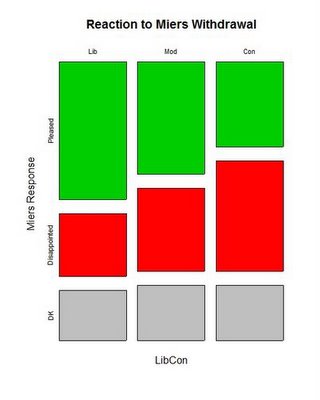

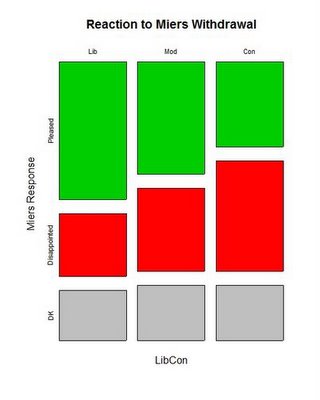

The Gallup/CNN/USAToday poll, taken 10/28, N=516, finds that response to the Miers withdrawal follows partisan and ideological lines, with liberals more pleased and conservatives more disappointed by the withdrawal.

The CNN story on the poll is here. Gallup has a

Frank Newport writeup of the poll here. (Free as of Saturday, but subscription required after that, I think.)The interesting thing is that the most vociferous opposition to Miers came from the most conservative wing of the Republican party, yet among the public conservatives were more disappointed than pleased by the withdrawal. How come?

One simple partisan answer would be that liberals like seeing the President twist slowly in the wind, while conservatives are disappointed by anything that hurts the President. While plausible in general, this story line doesn't address

the giddiness at the National Review web site on Thursday morning:

CORKS [Kathryn Jean Lopez]

I'm getting some of those e-mails too. But no champagne here. No gloating. Just relief. It was the right thing to do--withdraw--and it has been done. Super. Was this whole thing unnecessary? Yes. But I don't think that's our fault. The nominee made no sense. So it's over. Live and learn. Posted at 09:34 AM

RE: CORKS [Jonah Goldberg]

Kathryn -- That would be easier to buy if you weren't wearing a giant party hat and drinking out of your shoe and Chaka wasn't in the mailroom snockered out of his gourd xeroxing his butt. But, yes, you're right. Blessed are the peacemakers.

Posted at 09:37 AM

As any regular reader of conservative opinion can attest, the criticism from the "Intellectual Right" was overwhelming, and based on both Miers judicial philosophy (or lack of same) and limited qualifications compared to many other prominent conservative jurists and legal scholars. Among "Social Conservatives", criticism more commonly focused on whether Miers was a reliable conservative, or might show a moderate-to-liberal streak that would not provide the kinds of outcomes that are of most concern to social conservatives. So whether one is a reader of The Weekly Standard or Eagle Forum (or a daily listener to Rush, for that matter), the message was the same, a poor choice who should be withdrawn.

Pitted against these conservative messages were those coming most prominently from President Bush himself, and the White House, combined with those religious conservatives such as Dr. James Dobson who spoke in favor of Miers. Both the White House and its surrogates talked about Miers religious faith, evangelical views and the "near unanimous" opposition to abortion in her church.

So the messages from conservatives and Republicans were quite divided in their valence towards Miers' nomination. What about the liberals and Democrats?

Some prominent Democrats, most notably Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, supported Miers but the vast majority remained quiet or expressed concerns. But none launched a full attack against her qualifications or judicial philosophy.

So what does this configuration of elite messages suggest about public opinion in response to Miers? The most important point is to appreciate how little attention the mass public pays to complex issues such as this that delight Washington and us political junkies. As

a previous post here mentioned, the level of "don't know" response to Miers averaged over 30%. But even that does not mean that the 2/3 who did express an opinion about her nomination understood the context of the debate elite opinion makers were waging. The nature of the mixed signals that were coming from elites suggests that the public was even less able than usual to make sense of the Miers nomination and its issues.

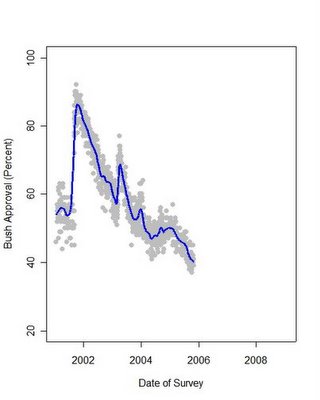

UCLA political scientist John Zaller, author of "Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion", argues that citizens look to elite signals for considerations that support their positions. When the message is entirely one sided (think aftermath of 9/11) then the public moves more or less uniformly in the direction of elite consensus. When there is division, citizen look for cues as to who to believe. The most prominent of these are partisan cues. Here think of the run-up to the Iraq war. A unified Republican party sent unambiguous messages to Republicans and conservatives in support of the war (despite a considerable isolationism visible two years earlier in the 2000 campaign.) The Democrats sent a mixed message, with both supporters and opponents of the war. Mass opinion was overwhelmingly in support of the war as a result, with much more division among Democrats in the mass public than among Republican partisans.

So what happens when both parties are sending mixed signals, as in the Miers case? Conservatives and Republicans would be exposed to two conflicting messages-- both from usually trusted sources. Because most people pay limited attention to politics, the President's message would be expected to affect mass Republican opinion more, simply because even among Republicans only a small proportion are avid consumers of conservative sources such as George Will, The Weekly Standard, National Review, the Wall Street Journal or Rush. A secondary source of information was through the "mainstream" media coverage of the controversy, which Fox, CNN, MSNBC as well as the broadcast networks made prominent parts of their coverage. The upshot is that any conservative or Republican had to decide not only who to believe but also to sort out what the issues really were. The difficulty of this task was guaranteed to produce a split in conservative opinion, with the advantage going to the best known, most widely visible, and most familiar source-- President Bush. However, the counter message was also available and produced a significant split in opinion. The result, a split among conservatives of 34% pleased with Miers withdrawal and 44% disappointed. Such a small edge to the President's position is testimony to the strength of the conservative critique of Miers.

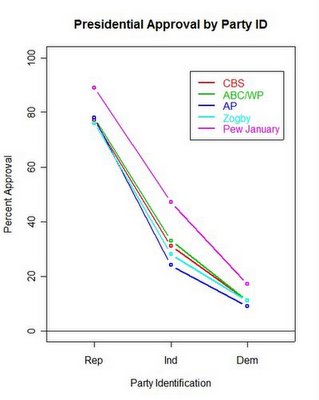

Among Democrats, the message was much more muted. Despite a few supporters, such as Reid, the overwhelming response was... silence. Democratic leaders stood on the sidelines and watched the Republican death match. As a result, Democrats failed to send strong signals that a Miers defeat (or withdrawal) was clearly a good thing (for their side), but they didn't send a strong signal in favor of her either. This left the mass Democratic partisans to fall back on their partisan perception of the debate, and overwhelming disapproval of President Bush, in order to judge the meaning of the Miers withdrawal. The result was Democrats and liberals were a bit more united in their response to the withdrawal than were Republicans and conservatives-- a rarity in itself. Liberals split 55% pleased to 25% disappointed, while conservatives split 34%-44%.

Roberts drew enough Democratic support that the partisan response to him was relatively muted, while Republicans were nearly unanimous in support. Republicans split 68-8% in favor of Roberts, while Democrats were evenly divided 31-33% in a

Pew poll taken September 8-11, just before the Senate hearings.

Both of the Miers and Roberts figures would be expected to be more extreme with more typical homogeneity of partisan elite messages. If the next nominee provokes unified partisan messages, we should expect to see a much more divided response in mass opinion.