Now UPDATED with polling completed through January 22, 2006. Newer comments appear at the bottom of this original post.

Now UPDATED with polling completed through January 22, 2006. Newer comments appear at the bottom of this original post.Canada will hold federal elections on Monday, January 23. Liberal party Prime Minister Paul Martin disolved parliament on November 29, setting off the election campaign. Among other issues, this election will offer the public a vote on the Liberal party's handling of the "Sponsorship Scandal" which has dogged the Liberal government for over two years. On November 1, 2005, Mr. Justice John Gomery released his report on the scandal. Prime Minister Martin had pomised in an April 21 speech to call elections within 30 days of the release of that report.

For much more detail on the Sponsorship Scandal and the Gomery report, see the coverage at the Globe and Mail here.The data presented here are taken from the

exceptionally good web pages of Nodice.ca here. Their coverage of the election goes well beyond the polling data and is very much worth reading. Meanwhile, I'll focus on the polls.

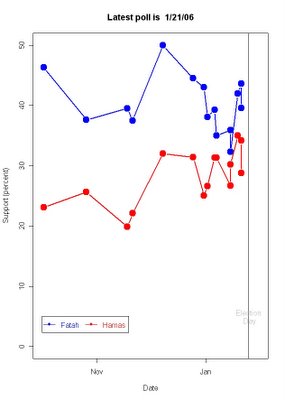

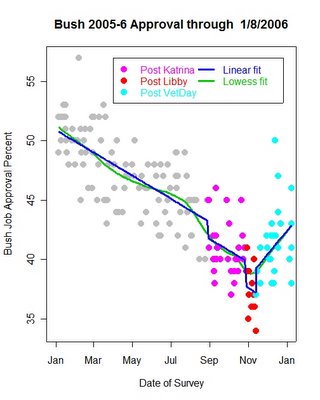

The top panel of the graph above shows the trends in party support since the last federal elections, on June 28, 2004. The sold round points indicate the last election results in popular vote. The open circles are poll results since then and the solid lines are the trends in party support, estimated by a local regression (lowess) fit. Vertical lines are labeled with major events in 2005. Justice Gomery conducted his investigation throughout the spring of 2005. On March 29 he imposed a publication ban on certain testimony, provoking a great deal of press circumlocution. The ban was lifted on April 7, unleashing especially harsh evidence against the conduct of the previous Liberal government. As is apparent from the graph, the result of this news was a 10 point drop in Liberal support while the Conservatives enjoyed a 5 or 6% increase in support. This was short lived, however. Prime Minister Martin gave a speech on April 21 describing his efforts to rectify the scandal, argued for the importance of allowing Justice Gomery's full report to be completed and published, and promising to call new elections within a month of the publication of the report. The Liberal government survived a confidence vote on May 19, by a one vote margin-- with the Speaker breaking a tie.

Following the confidence vote, liberal support settled in a range a few points below its previous equilibrium but considerably higher than during the worst days following the publication ban. Conservative party support sank back to it's earlier equilibrium. This status quo was maintained until the Gomery report was released on November 1, when the Liberals suffered a modest and seemingly short term, downward shock, while the Conservatives picked up a couple of points.

In the campaign period so far, there has largely been stable support for the parties. The first two of four debates were held December 15 (French) and 16 (English) but produced no immediate shocks in the polling. The next two debates are scheduled for January 9 and 10.

Pollsters largely took the Christmas to New Year's holidays off. The latest two polls offer a split view-- one with a Liberal-Conservative gap about equal to the pre-Christmas polls, with the other showing a tightening to a statistically insignificant difference. This should become more clear as polling resumes with the new year.

There is some evidence in the polling that Conservative strength threatens to drive suporters of the National Democratic Party into voting strategically for the Liberals. There is a slight downward trend in the NDP's poll standing, though again a need for more post-holiday polls to be more confident of that trend.

The Globe and Mail has an interesting story on this possibility here. Finally there are large regional variations in support, most obviously for the

Bloc Québécois, but not limited to them. We'll take a look at that another time.

The polling links at Nodice.ca provide full details for those who can't wait.Update (1/5/06):The post-New Year's polls seem to confirm the tentative trend we saw in the last polls of 2005. The Liberal lead has vanished and the Conservatives are at least tied and quite possibly ahead. In the bottom half of the figure above, the trend lines have clearly shifted to favor the Conservatives. This reversal of fortune is striking as the first substantial movement of the campaign. It is also damnably frustrating that it appears to have started during the lull in polling over the Christmas and New Year's holidays, so we have missed the chance to see the move from the beginning.

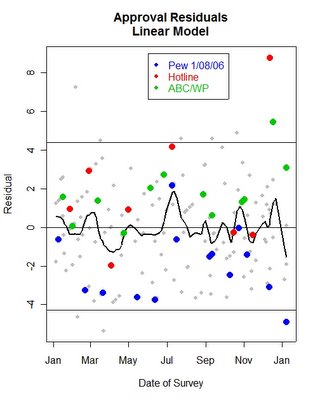

A technical concern and caution about the above figure is in order, however. The lowess trend lines I present above are sensitive to the last data points in a series, especially when there are relatively few observations and, as in this case, the last few observations are separated from the earlier data (due to the lack of holiday polling.) For these statistical reasons, we should consider the latest trend line to be extremely tentative. It clearly reflects the surge in Conservative support, and the loss of Liberal backers, but the trend cannot be estimated very precisely without more post-New Year's observations. I am sure the pollsters will oblige us with more data shortly.

Update (1/6/06):Several new polls ending 1/4 have now been added to the data.

The Conservative lead now appears to be about 2.5% based on the local trend lines in the figure. There is also some hint that the Liberals' decline may have started to stabilize. Once more, however, we should be cautious about the rate of change with so few January polls.

And one small technical note: the dates I give for polls is the last day the poll interviewed people. Reporting of poll results on the web sometimes gives the date of the publication of the poll, rather than the last polling date. I try to be consistent and only use the date of last interview. This makes the results look "older" but is more properly a reflection of when the polling was done.

Further update (1/6/06):Just as I posted today's update, I got the new CPAC/SES tracking results for 1/5. They've now been added to the figure. SES finds the surge for the Tories peaked on 1/3 at a 3 point lead, 36-33. Since then their tracking has found a 2 point lead on 1/4 and now a 1 point lead, 34-33 as of polling ending 1/5. In those three days Liberal Party support has been constant at 33%.

The trend lines in the graph above suggest that the Conservative rise has continued, but no other polls completed on 1/5 are yet available to see if others verify the stabilization or even decline of the Conservative lead. My estimate remains at 2.5%, for now. Stay tuned.

P.S. See Matt Shugart's comment here and his

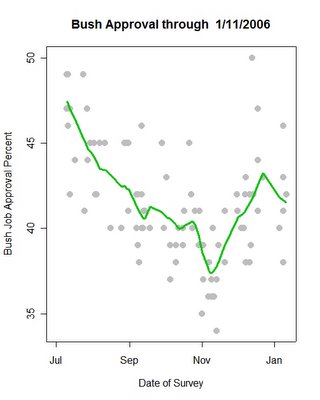

posts on the Canadian election at Fruits and Votes here.UPDATE 1/9/06:New polls through Jan. 8th make it clear that the surge by the Conservatives and the slide by the Liberals has continued. Last update the Liberals appears to be flattening out, but as of the Jan 8 polling, it is clear that their decline continues. The gap is now about 3.5% in my local trend estimate. Some polls have it as high as 8% or as low as 3%. My trend estimate is an attempt to smooth out the random poll-to-poll variation, hence it is less extreme and a little slower to respond to short term movements.

I'll be out of the U.S. for the next week and may not be able to keep this updated while I'm traveling. In addition to the polling links mentioned above, http://www.canadawebpages.com/pc-polls.asp is very good. Thanks to Mahigan who pointed this out to me in a comment.

Update, through polling as of 1/10/06:I've just managed to update the election tracks through the 1/10 polling dates. The surge by the Conservative party appears to continue and to grow while the Liberals continue to sink. This is a remarkable run of improving polls for the Tories given what stability we saw in the polling before New Years.

Because I'm in Israel and have a very full schedule of meetings, and a very balky wireless connection (if you stay at the King David hotel in Jerusalem beware the wireless server!) , I've not been able to keep up with the news of the second set of debates, let alone see them. Given the trends here only include data collected through 1/10, these effects ONLY include a small part of the effect of the second round debates. The rolling nature of the sample means only 1/3 of the sample could have been exposed to the third debate and none of the sample to the fourth debate. Therefore these trends are substantially "pre-third-debate" and so give us a very poor reading of the response of the public to these last two debates. What can certainly be said is that the Conservative party came into the debates with all the momentum and a significant lead in the polls. As the story unravels over the next few days of polling we will see the impact of the debates emerge.

I'll still be travelling for a while so updates will remain slower than I would wish. Keep your eye on http://www.canadawebpages.com/pc-polls.asp for a decent graph and up-to-date data in the meanwhile. (But do check back here-- I'll update every chance I get.)

Update, polling through 1/11/06:The conservative lead remains strong after the final debate. Both the Conservative climb and the Liberal decline appear to continue. One wonders if there is a floor for the Liberals or a ceiling for the Tories. Certainly there is still no evidence of a debate impact, either to spur on the Conservative lead or to provide a rally for the Liberals.

I'll be away from an internet connection until Sunday night, so unless there is an internet cafe in the Golan Heights, I probably won't be updating this for a couple of days.

Update, polling though 1/13/06:There isn't a lot of dynamics at this point. The Liberal Party's slide looks to have stabilized at 28-29% while the Conservatives are consistently polling at 38-39%, almost exactly the reverse of their support at the start of the campaign and representing a quite dramatic reversal of fortune. One topic I've not been able to look into from the road is the geographic distribution of the vote and how the seats are likely to be distributed. Others have looked at this and it is in the end more important that the popular vote.

Update, polling through 1/14/06:No visible change since the 1/13 polling.

Now updated with both CPAC-SES and Strategic Counsel polls through 1/14. But still not visible change. Both parties seem to have flattened out.

I'll be in the air much of the next 48 hours so will be lucky to have time to post after bedtime tonight, but should be back in the U.S. on Tuesday and will update as promptly as possible through election day.

Update, polling through 1/17/06:There has been a slight decline in support for the Conservative party, with a corresponding upturn in support for the NDP, over the past three days of polling. After a long period of stability support for the Tories has fallen a little over a percentage point, based on the local regression trend lines in the figure above. Meanwhile the NDP has gained almost two points in support. Support for the Liberal Party, however, appears unchanged.

Update, polling through 1/20/06:After polling earlier in the week suggested a decline in support for the Conservatives, the last three days of polling suggests more stability in the Conservative lead over the Liberal party. The NDP does appear to have gained a bit this week.

Final pre-election update, polling through 1/22/06:The last seven days have seen stability in support for Conservatives and Liberals, and a modest rise in support for the NDP. Today (1/23/06) we get to see what the voters have to say, and to measure the accuracy of the polls.

But first, let's back off and take a look at the entire campaign and the perspective of longer term trends. While the basic pattern of support has been stable for 10 days or so, the dramatic story of this election campaign has to be the rise of the Tories and the slump of the Liberals. The two parties have almost exactly reveresed their positions since elections were called on November 29. The shift of fortune by about 7-8% for each party is a substantial amount of change during a campaign. This markes the 2006 election as one of particular interest for understanding campaign dynamics.

The most frustrating aspect of the data is that the shift in party support took place most dramatically during the Christmas-New Year's holidays when little polling took place, and when we might normally think that voters minds are elsewhere. So a period that would be expected to produce little political change (and hence when little polling should be needed) turned out to be precisely the time when substantial numbers of voters changed their minds about the two leading parties. Individual level data from those polls will be necessary to tease out the sequence and possible motivations for change, but the "blank spots" in the graph between December 22 and January 3 will remain frustrating to analysists.

A second way to look at the dynamics is to return focus to the top half of the graph, one that I have ignored for too long. Here the time scale is that of this government. On this scale, the long periods of political stability are marked by two periods of dramatic, though short term, change. The first came in the spring of 2005 during the Gomery investigation of the "Sponsorship scandal". At that point the Liberals slumped suddenly by 10 points, from 40% to 30% support, only to then recover most of their original support following the confidence vote they won by a single vote. The Conservatives saw a smaller rise, but almost immediately lost their gains to fall back to their original support of 28-29%. The two leading parties remained locked at those levels of support up through the dissolution of parliament November 29. But what appears as gradual change in the lower panel of the figure, is revealed to be extremely rapid change in the top panel. After an initial pause, the shifts in party support are even steeper than those during the Gomery investigation last spring.

The impact of the Gomery investigation in the spring was a preview of the vulnerability of the Liberal party. But the puzzle is that when the Liberals barely survived the confidence vote on May 19, their support returned to nearly their pre-investigation levels, as did the Conservative party support. There was only about -2% long term cost to the Liberals, and Tories received no gain at all from the scandal. Yet when the election campaign came, the damage to the Liberals and the strength of the Conservatives came back to produce the dramatic change we see in the top panel. So were the Liberals simply "walking dead" waiting to fall down, or did the Tories find the right issues and campaign themes to destroy the Liberal advantage over the course of about 10 days during the holidays?