(Click the figure, then click it again to see the full resolution.)

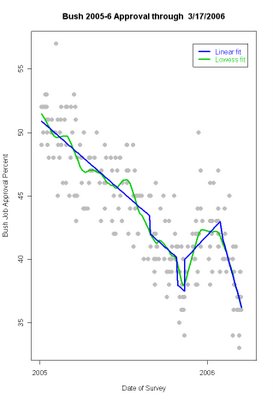

Partisanship is a moving target over time and exhibits considerable variation across pollsters. The combination of both over time and across pollster variation makes simple comparisons of partisan balance across polls potentially misleading and agreement on a single partisan distribution difficult at best.

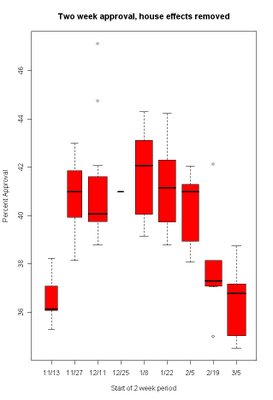

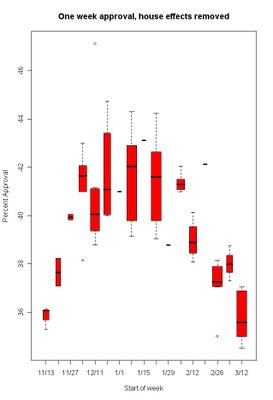

Between January 1, 2005 and March 12, 2006, Republican partisan identification declined by an estimated 3.6%. The percentage of the adult population calling themselves Independent rose by 4.6%, and the percentage of Democrats declined by a statistically insignificant 0.4%. These changes are important for polling methodology and also present a politically important shift in the partisan balance.

In the first post of this series on partisanship (here), I showed that pollsters differ substantially in the percentages in each partisan group their polls typically find. In this post I turn to change over time. While much more stable than many political attitudes, party identification is not immune to systematic variation over time. This makes the party id distribution for any pollster a moving target, while posing the problem of how to know what the target is at any given moment. This is particularly an issue for those who think polls should be weighted to a constant distribution of partisanship, or even to a moving average of previous polls. Perhaps more importantly it means that those who judge a poll's merit on the basis of it's partisan balance need to be much more aware of how much variation there is, even over the relatively short span since President Bush's reelection. Differences between polls that are pointed to as signs of at best “bad samples” and at wost malignant bias by pollsters are in fact well within the range of variation typically found across polls and over time.

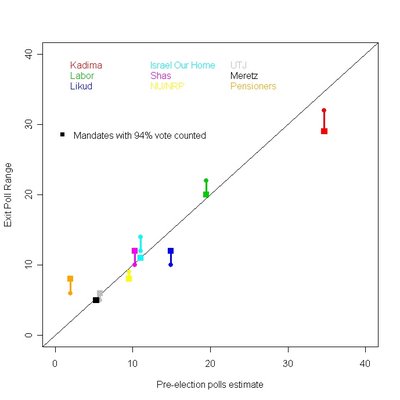

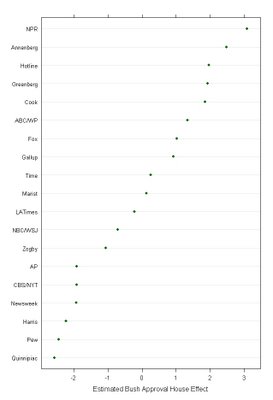

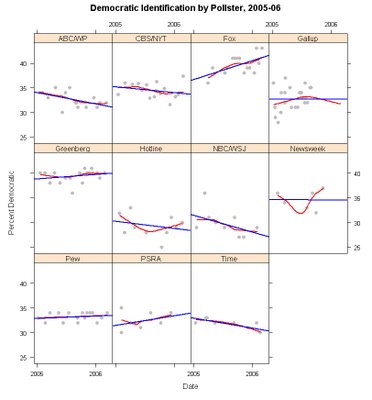

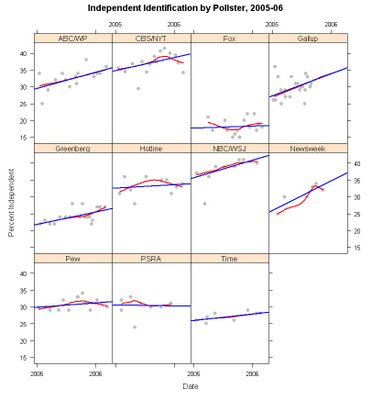

In the figure above, I plot the trends in Republican identification through 2005-06 for all pollsters for whom I have sufficient observations to make reasonable estimates. (The AP is omitted because their results are generally only available in a “leaned” form, with Independents who lean to either party included in the party totals. The data here are only for “unleaned” question formats.) The “house effects” are clear in the range of vertical variation across pollsters. Fox is quite high (they are also high on percent Democrats) while NBC/WSJ is quite low (they are also low on Democrats.) And the others vary between these extremes. As we saw in my previous post, most of the variation across polls is related to the percentage of Independents. Fox gets few Independents, and is thus high on both Reps and Dems. The Fox question wording does not offer an explicit “Independent” alternative, which surely accounts for this difference. NBC/WSJ is quite high on Independents, and so is low on both partisan groups. There is no obvious question wording that would explain this consistent house effect.

More importantly, however, all of the pollsters show a downward slope over the course of the 14+ months included here. While there is substantial variation in what the percentage of Republicans is at a given moment in time, all the polls agree that this percentage has fallen since January 2005. The straight line in each panel is the linear estimate of trend over time. The red curved line is a local regression that can provide a non-linear fit to change. While the trend is somewhat non-linear for Fox and Gallup* in particular, and a bit off of linear for CBS/NYT and perhaps NBC/WSJ, in most panels the trend is pretty close to linear regardless of which estimator is used. Also the slope varies across the polls, but not hugely. A statistical model that allows the slopes to vary (along with house effects) is not statistically distinguishable from a model that assumes equal linear slopes (but with different house effects for the level of Republican identification.)

(*Gallup data requires explanation. Gallup does not routinely release the partisan breakdown on their polls, at least not that I've been able to find. They do list partisanship breakdowns for all polls on their subscription only website. The data I display here is taken from the Roper Center at the University of Connecticut's “iPoll” database, which is available to subscribers and which includes permission to publish results of research based on the data. My university is a subscriber. Those data end in September 2005. As an individual, I am a long time subscriber to the Gallup website but do not wish to publish data they do not consider available without fee to anyone on the web. I've therefore used their data through March 2006 in my statistical analysis, and in the fitting of the regression and local regression lines in the above figure, and those that follow. However, to honor their desire to protect their data from release, I've suppressed the plotting of data points in the Gallup series after September 6, 2005, the last data available to me from the Roper Center. As is clear from the figure, Gallup data show a Republican decline through September 2005, but this flattens out after that. I believe it would be misleading not to show the trend based on the entire dataset so I've included the linear and non-linear trend lines estimated on the full dataset but have not plotted the data points themselves after early September. You will have to take my word for it that the Gallup data after September scatter more or less randomly around the non-linear trend line. The linear fit is not terrible but does under-estimate Republican identification for the Gallup poll late in 2005 and in 2006.)

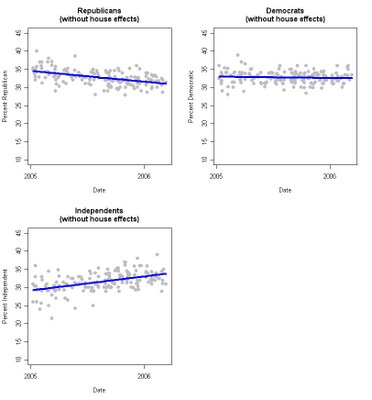

By pooling the data across polls, and fitting a linear model with dummy variables to capture house effects, I estimate that Republican identification was 34.6% on January 1, 2005 and 31.0% as of March 12, 2006. That is a small change compared to shifts in presidential approval over the same period, but is a statistically and substantively significant shift in the relatively more stable partisanship measure.

Paradoxically, the loss of Republican identifiers should be helping President Bush's approval rating among “the base”. If those shifting out of Republican and into Independent are very marginal Republicans, then their support for the President should be less than that among stronger identifiers. By leaving the party, they avoid dragging down presidential approval among the remaining GOP identifiers. For example, in recent Gallup polls approval among Republicans has been around 80%, and about 30% among Independents (roughly speaking). If we added back to the GOP the 3.6% they've lost, and if they behaved like other Independents, then approval among the GOP would be only 74.8%, not the current 80%. So that isn't a huge amount, but it is noticeable. (Of course, the 3.6% might not be typical of other Independents, so the effect could be less. But you get the idea.)

These estimates are based on samples of adults. The 2004 exit polls estimated a Republican share of 37% among actual voters, a modest advantage for Republican turnout. Election day was 59 days before January 1, so my estimate would be 35.1% Republican on election day, if the trends in 2005-06 extended back to election day 2004, within 2% of the exit poll estimate.

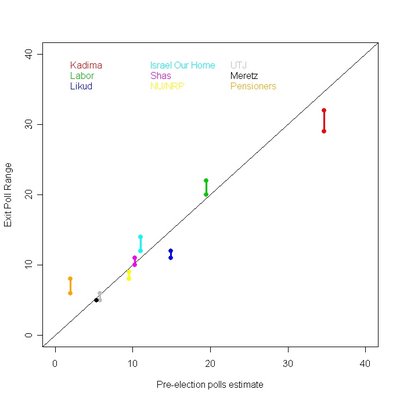

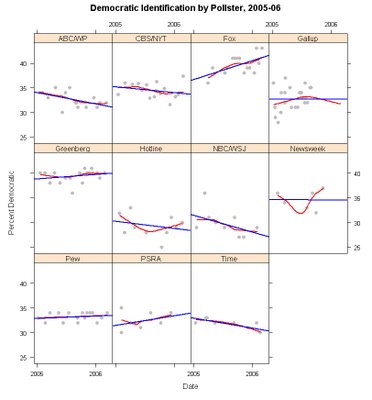

In contrast to Republican identification, the percentage of Democrats has remained quite stable in most polls since January 2005. The figure below shows the trend in Democratic identification using the same methods as for Republicans above.

The variation in slopes over time are generally modest, with the exception of Fox and NBC/WSJ. Once more a statistical test fails to find convincing evidence that the trends differ significantly across polls. (The Fox upward trend is likely related to the question wording. I discuss this below.) When pooled across polling houses, and taking account of house effects, the estimate is that Democratic identification is statistically flat over this time period, with a non-significant decline of 0.4%. By these estimates, Democrats made up 32.9% of the adult population on January 1, 2005 and 32.5% on March 12, 2006. Here the gap with the 2004 exit polls is larger. The exit polls estimated that Democrats and Republicans both made up 37% of the voters on election day. Based on these 2005-06 polls, the Democrats were about 4% lower than this in the population, at least as of January 1, 2005. In the last 14+ months, the Democrats appear essentially unchanged, despite the bad times for President Bush and the losses suffered by the Republican identifiers. So what about Independents?

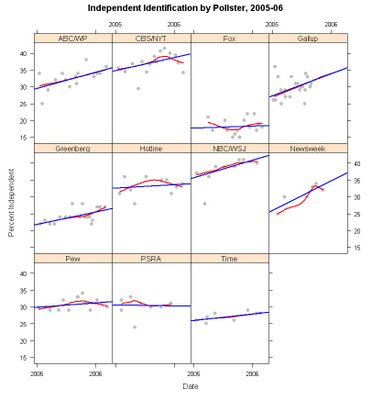

Independents have grown in size across most of the polls. PSRA (Princeton Survey Research Associates) has them flat, and Fox has a small slope but every other poll shows small to substantial gains in Independent identification over the last 14+ months. The gains are essentially linear, as the local regressions lie very close to most of the linear fits. And a statistical model again finds that a model in which Independents gain at a common rate across polls cannot be rejected (with house effects for level but not for slope.) Based on the model, Independents have moved from 29.2% at the start of 2005 to 33.8% as of March 2006, a 4.6 percentage point increase.

There is a considerable debate in political science over how malleable partisan identification is. I belong to the camp that argues for significant responsiveness of party id to the policy positions of the parties. Others (Morris Fiorina, and the team of Bob Erikson, Jim Stimson and Mike MacKuen, for example) argue that party identification responds to government performance of one kind or another. We all agree that partisanship can shift in non-trivial ways over relatively short periods of time. There is another side, led by Don Green and colleagues who argue that party id is actually very, very stable and except for some random measurement error is really not responsive to other political forces. We'll leave that discussion for another day.

When shifts occur in party id, it is reasonable that those most likely to shift categories on the partisanship question are those in or near to independence. (There are arcane academic debates on exactly why this is, but in the big picture it seems reasonable enough that those with the weakest attachments to parties would be most likely to shift when given a reason.)

So how does that help us with the data before us? In 2004 the presidential election favored President Bush who won by a small but comfortable margin in the popular vote. If we assume this is because short term forces favored the Republican candidate, it is reasonable that some people who are near the dividing line between independence and Republican identification were moved to shift a bit to their right, into declaring themselves “Republican” when asked “In politics, as of today, do you consider yourself a Republican, a Democrat, or an Independent?”, the Gallup form of the question. In 2005 and so far in 2006, the balance of forces has been against the President and the Republican party. The result should be that those who were moved a little into the Republican category during 2004 are now likely to move out and into independence. The result is a downturn of Republican identifiers and a growth in the proportion of Independents.

What about the Democrats? The 2004 election was one of the most polarizing elections in the last 60 years. It would seem plausible that some Independents who lean towards the Democratic party were convinced to declare themselves “Democrats” as a result of this polarization. When the election period was over, we might normally expect these people to drift back into independence as well, resulting in some decline in Democratic as well as Republican identification. However, the bad year for President Bush has produced political forces consistently disadvantaging the Republicans, and hastening the departure of especially weak identifiers. At the same time these forces should act to hold the most marginal Democrats in the party, keeping them from drifting against the tide of partisan forces over the last year or so.

Of course, we don't have individual level data, so this is a plausible explanation, not one that is beyond debate. We would need to see which individuals shifted to be confident that my story is correct. With only these aggregate data it is possible that some other, more complex, interchange among the three partisan groups has occurred. The net effect, however, is not in doubt: fewer Republicans, more Independents, about the same number of Democrats.

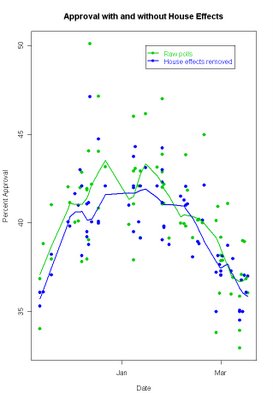

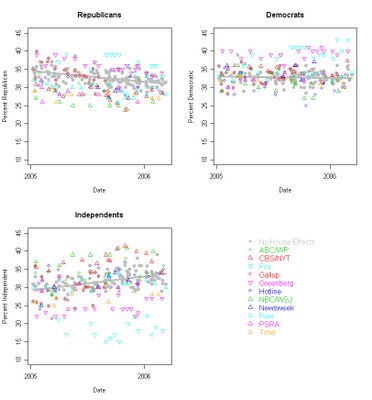

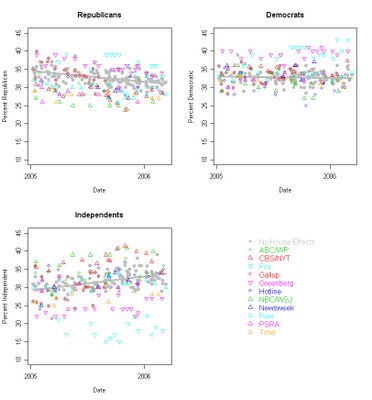

But how much spread is there across polls, and what happens if we take out the house effects to our view of partisan trends. The figure below shows each partisan group over time, with the observed data and with a trend (in gray) of what we would estimate partisanship to be having taken out the house effects using my statistical model.

The spread of partisan estimates is considerably larger than the spread of estimates with house effects removed. This is especially striking for the Independents, where the house effects are huge. The very low percentage of Independents in the Fox poll is undoubtedly due to their question wording, “When you think about politics, do you think of yourself as a Democrat or a Republican?” The lack of an explicit “Independent” option would be expected to drive down that category, and it clearly does. While not quite as extreme as the results from allocating partisan “leaners” to a party, the Fox question results in a distribution that appears much more partisan for both parties than other polls. NBC/WSJ has the opposite result. Their question is seemingly innocent, “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a Democrat, a Republican, an Independent, or something else?” They don't get many “something else's”, only about 4%, yet their Independent group is quite large relative to other polls. This could be due to interviewer training, I suppose, but the large number of Independents is something of a mystery to me (unless interviewer's encourage “something else” respondents to choose Independent before recording the response. Based on other polls with a “something else alternative, this could add 6-8% to the Independent category. Still, that wouldn't explain the low numbers of Dems and Reps that NBC/WSJ get.) The result is that NBC/WSJ is consistently low on both Republicans and Democrats. Other polls fall between these extreme house effects.

The gray dots and trend line shows what the distribution of partisanship would be if we remove the house effects but keep the common trend over time. The distribution is reasonably tight about the trend, certainly compared to the raw polls.

These figures should make clear why comparing party identification across different pollsters and/or at different times is a dangerous business. It is certainly true that house effects differ and they differ substantially. So compared to Fox, everyone else has too few Republicans. Of course, they have too few Democrats as well! The problem is there are house effects but more importantly we don't have any single “correct” value for party identification. The figures here demonstrate that there is great variation, yet who is to say that any one of these pollsters is “right” and the others wrong? The technology of polling is essentially shared by all. I deny that anyone seeks to intentionally ask biased questions. Rather question wording variation reflects the purposes of the survey organization, and these may differ for legitimate reasons, as when Fox leaves out an Independent option, or when some pollsters offer a “something else” alternative or stress “Generally speaking...” as opposed to “In politics as of today...”. These produce different results, but none is clearly better or worse than the others.

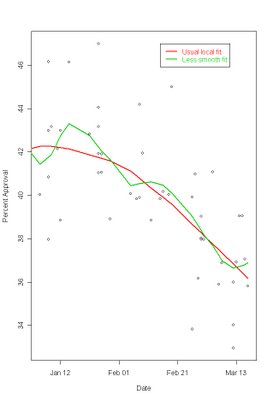

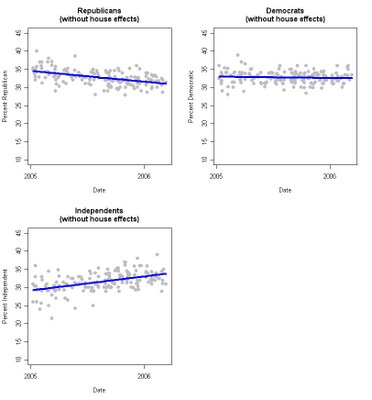

So if we can't agree on a single standard, what can we do? We can estimate the house effects, and compute a pooled estimate normed to a single survey house. This figure appears below (and in gray in the figure above as well.)

Here (and throughout this analysis) I've used Gallup as the reference pollster simply because Gallup does more surveys than anyone else in my dataset and it makes sense to use the house with the most cases as the base. This does not mean that Gallup has the “right” measure of partisanship. It is merely convenient.

If we wanted to weight datasets to a fixed partisan distribution, this figure shows the problems we encounter, even after pooling across 165 surveys. First, there is a trend. Weighting to ANY static values for partisanship will be wrong if partisanship actually moves, as the data here demonstrate. If instead you use a moving average of past polls, you'll always have estimates behind the current point on the trend line. So you could use the regression estimate for the current party balance, which still uses the past but requires a good fit to the trend. As it happens we do have a good fit to the linear trend here, but there is no reason to think that is guaranteed in the future. And while these trends are not extremely sharp, they do imply a shift of 3.6% down from Republicans and 4.6% up among Independents. Some strong words have been used to describe polls as “biased” for differences of this magnitude compared to what the antagonists think are the “right” numbers. So that is a non-trivial issue.

Second, the variability around these regression lines suggests uncertainty of about +/-4% even when we leverage all our data as much as we can. My estimate of current Republican identification is 31.0%. But I can't say with any confidence that it is not 28% or 29% or 33% or 34%. Or maybe even 27% or 35%. And this is after taking out all house effects and allowing for change over time.

Some argue for weighting to the exit polls, which is ironic in light of all the criticism of exit polls after the last three elections!

My point here is not to take sides on the weighting to party id issue (though my analysis is relevant) but rather to point out how difficult it is to have a target party distribution that is precise enough to have absolute confidence in (which is what you need if you are going to weight to it.) We are pretty darn sure what the percentages by education, sex, race and region are in this country. Those make good weighting criteria. Not nearly so good an idea for party, no matter how you care to measure it.

Finally, there are some that argue that even the variation around the trend line in the figures is evidence of systematic response to political events. While I cannot distinguish this from random noise, it is possible that some of this variation is “real”, but very short term, change Weighting to an unrealistically stable target might avoid partisan criticism but would also distort the actual variability of public opinion.

To conclude this look at party over time, as Galileo said, “it moves.” Right now that is working to disadvantage the Republicans, but not so much in favor of the Democrats. The rise in Independents may itself change if they are pushed more strongly towards one party or the other.

Click here to go to Table of Contents