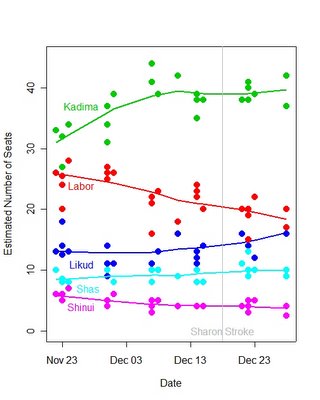

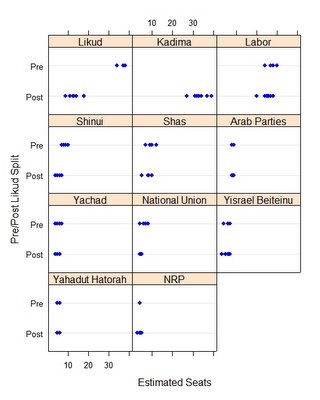

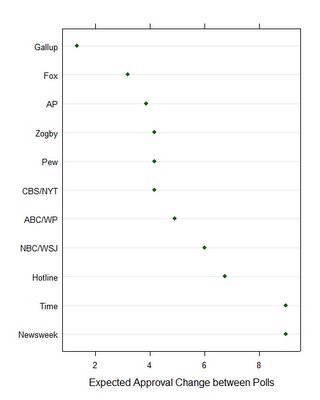

The above graph shows the expected change between polls in presidential approval given the current trend of +.15% per day and the average spacing between polls in 2005 by various polling organizations. The more frequent the polls, the less change on average between consecutive polls. The less frequent the polls, the more likely successive polls will "find" large changes in approval. This makes some polls appear more stable and others less even though the actual daily rate of change in approval is exactly the same for all polls. (

What's a "lede"? Click here!)

Polling organizations vary dramatically in the average number of days between polls. When approval is trending either up or down, the amount of change between polls depends on how often the poll is conducted. This difference poses problems for how reporters frame the results of polls, as reporting this week has dramatically demonstrated.

On Tuesday, December 20, readers were confronted with two seemingly incompatible stories about President Bush's job approval rating.

The Washington Post had it this way:

Bush's Support Jumps After a Long Decline: More Americans Upbeat on Iraq, Economy

By Dan Balz and Richard Morin

President Bush's approval rating has surged in recent weeks, reversing what had been an extended period of decline, with Americans now expressing renewed optimism about the future of democracy in Iraq, the campaign against terrorism and the U.S. economy, according to the latest Washington Post-ABC News Poll.

CNN had a rather different lede:

Poll: Iraq speeches, election don't help Bush

CNN -- President Bush's approval ratings do not appear to have changed significantly, despite a number of recent speeches he's given to shore up public support for the war in Iraq and its historic elections on Thursday.

(Sadly,

PoliticalArithmetik used essentially the same headline here.)

Such dramatically different interpretations of polling data contribute to public distrust of polls and the suspicion (seemingly universal in both left- and right-leaning blogs) that polls are widely manipulated to suit biased media agendas. Oddly, at the same time, poll results that support the blogger's own preferences are immediately embraced as "proof" that Bush is either surging dramatically or reports of surge are a myth, again depending on the blogger's preferences.

I've written extensively here over the past week about variability in poll results and when results are really out of line with other polling and when it falls within the limits of normal variation. But there is a different and systematic problem with the interpretation of poll results that deserves attention by those who report on polls.

Many, perhaps most, poll stories take their lede as in the above two examples by pointing out the change from the previous to the current poll. To say approval of President Bush is either up or down requires a comparison to some previous poll. Because news organizations sponsor their own polls, the point of comparison is almost always to that organizations own previous poll. But there is the rub. News organizations vary dramatically in the average time between their polls. In 2005 here is how many days elapsed between polls, on average:

Gallup 8.6Fox 20.7AP 25.1CBS/NYT 27.1Pew 27.1Zogby 27.1ABC/WP 32.0NBC/WSJ 39.1Hotline 44.0Newsweek 58.7Time 58.7Gallup polls are taken more than twice as often as the next most frequent poll, that of Fox News. Gallup is 3 times as frequent as CBS News and the New York Times, and 3.7 times as frequent as the ABC News/Washington Post poll.

So what happens when reporters compare results between editions of the Gallup and ABC/WP polls? If approval is trending up, as it is right now, then

on average, the ABC/WP change between polls will be 3.7 times larger than the change between Gallup polls, even when both are changing at exactly the same rate per day!Since November 11, approval of President Bush has been trending up by +0.1533% per day. Given the average spacing between polls, this means that consecutive Gallup polls would be expected to register gains of 1.3% while the average spacing for an ABC/WP poll means the average gain between their polls would be 4.9%. And that has

absolutely nothing to do with the real rate of approval gain, but only the spacing between the polls.

Now the average sample size of national polls implies a margin of error of about +/-3.2%. So what's your headline and lede for a story based on the Gallup poll? "

President Bush's approval ratings do not appear to have changed significantly" But if you write the lede for ABC/WP: "President Bush's approval rating has surged in recent weeks, reversing what had been an extended period of decline"

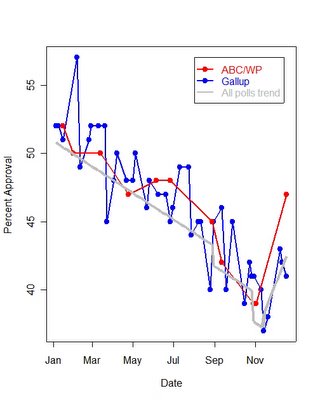

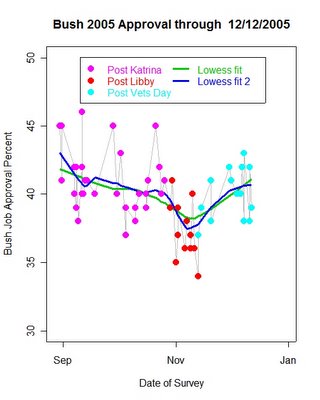

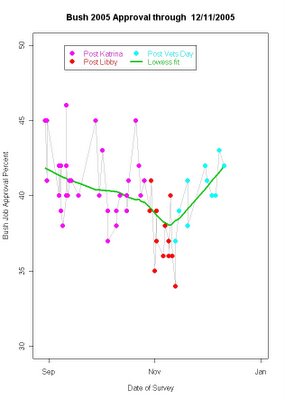

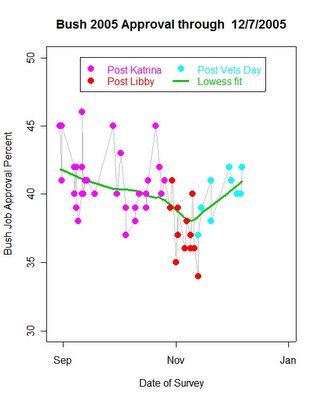

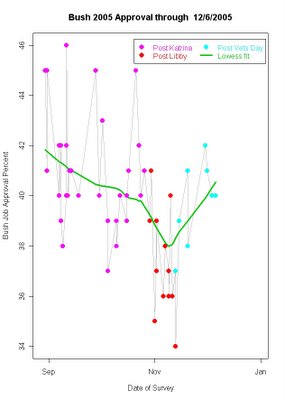

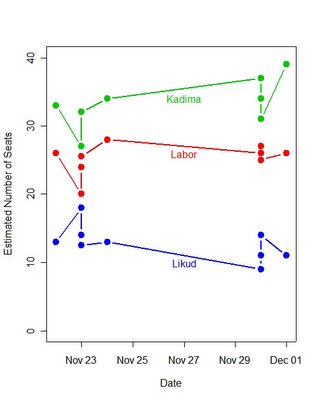

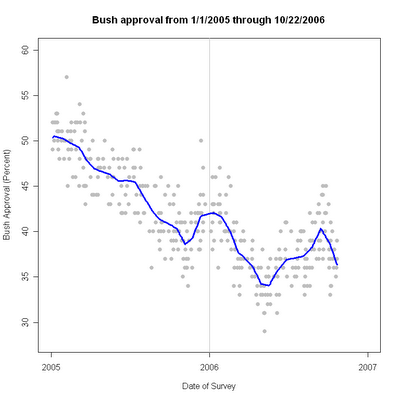

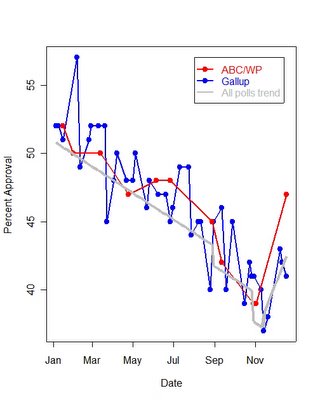

Let's take a look at the year-long trends in Gallup and ABC/WP. The figure below shows the two poll's path over the year and the gray line is the linear trend based on all polls taken this year, taking account of the shocks of Katrina, Libby and the post-November 11 aggressive White House response to its critics.

Both Gallup and ABC/WP fall a little above the linear trend of all polls, a well documented house effect that need not concern us here, but they track each other quite well. What is also obvious is that there are more blue dots for Gallup polls and fewer red dots for ABC/WP polls. But when the two polls are taken close together in time, they are usually pretty close to each other in results, certainly within reasonable margins for error.

So what do these two polls tell us has happened since late-October/early-November? Both show a substantial upturn in approval of President Bush. Gallup's three latest polls raise the question of whether approval is continuing to climb, but compared to Gallup's low points in early November, approval is clearly up. For ABC/WP, there are only two polls-- early November and mid-December. The upturn is more dramatic than Gallup's (though it's low point is also a bit higher so the gain in ABC/WP is +8% while Gallup's is +4%) but the conclusion is obvious from the figure:

both polls see an end to the year-long decline and a significant upturn since early November.The differences in these two stories' ledes is primarily a problem of journalistic interpretation of polling trends. Paradoxically, those who poll the most often, are least likely to find significant changes between pairs of polls, though they are more likely to capture short-term dynamics that other polls miss altogether for lack of data.

Because news organizations have a proprietary interest in the "branding" of their own polls, news stories lede with comparisons to their own past polls. But this practice is dramatically out of touch with the reality that the public is exposed to a large number of other polls. So when CNN writes that the current Gallup poll shows no change, they are implicitly forgetting the substantial trend over the past six weeks. When ABC/WP writes of a ratings surge, they are ignoring the fact that we've been reading 25 (twenty five!) other polls since ABC/WP did their last poll. Instead their lede is written as if there were no information about opinion in the intervening month and a half.

While no news organization will want to lose it's brand name poll, the practice of writing about polls without a context longer than "our last poll" and without a context "in relation to other polls" will continue to produce ledes that are an embarrassment when read side-by-side and which mislead the marginally attentive reader who needs the story to put the results in a meaningful context, both over time and compared to other results. One way to accomplish the first goal is for each story to come with a graphic showing that poll's history over the past year. This would also play to the strength of frequent polling by some organizations-- their graphs would look more informative and authoritative.

The second goal could be partially met if reporters wrote their ledes with the implicit acknowledgment that they had kept up with

PollingReport.Com (or better,

PoliticalArithmetik.) In that case, the ABC/WP poll could be cast as the

confirmation of trends seen in other polls. Note the air of authority! Others suggest the trend, but ABC/WP "confirms it as fact". That's not counter to branding concerns but is less misleading and seemingly unaware of 25 other polls.

P.S. A reader asked "What's a lede? It isn't in my dictionary." Thanks to them, I found

this very nice discussion of the journalist's term (a sign of my misspent youth) for the first sentence or paragraph of a news story.