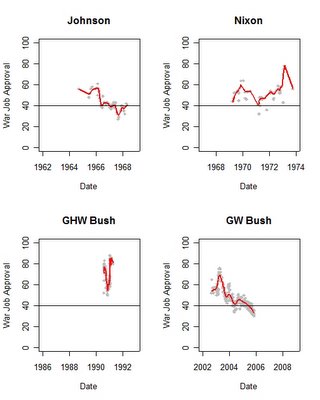

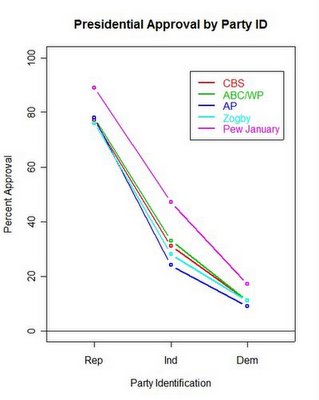

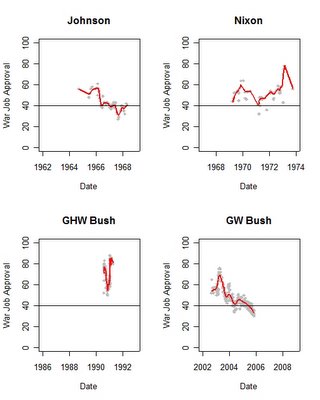

Approval of the job four presidents did in handling wars. The horizontal axis is scaled so the axes are comparable across presidents, which allows accurate visual comparison of the trends. Because of this, the scale may begin before a president takes office. Data are plotted only during a president's term.

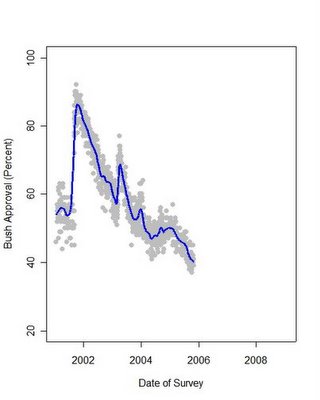

President George W. Bush's approval ratings on handling the war in Iraq deserve to be put in historical perspective. It is likely that any president presiding over a long term war will suffer declining approval ratings. This would be especially so when battlefield victories of the World War II type are impossible due to the nature of the conflict. A challenge of presidential leadership is to maintain support for U.S. military and foreign policy in such circumstances.

In comparison with three predecessors, President Bush's approval ratings more closely resemble those of Lyndon Johnson than those of Richard Nixon or the President's father, George H.W. Bush. While initial support for the Iraq war was a good deal higher than for Johnson's conduct of the Vietnam war, the subsequent decline in support is similar. Presidents Bush and Johnson both had approval ratings in the 60% range initially. In Johnson's case, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution and subsequent buildup of troops in Vietnam was not accompanied by a significant “rally effect” upturn in approval. President Bush, in contrast, enjoyed a large upturn in support in the early weeks of the Iraq war, with approval reaching 76% in Gallup's poll of 4/16/2003, a month into the conflict.

Subsequently approval for both presidents' handling of the wars declined to the 40% range. In Johnson's case, this approval remained relatively stable in the 40% range through the last 9 months of 1966 before dropping significantly in January 1967. Through 1967, approval of Johnson's handling of the war was mostly in the 30's, with a few polls as high as the low 40s and an all time low of 27% in August 1967. Approval appeared to improve a bit in early 1968 with Johnson's withdrawal from the presidential race and announcement of a bombing halt and a renewed effort at negotiations with North Vietnam, though the final reading was 41% in May of 1968. (No polling is available after that for Johnson's handling of the war.)

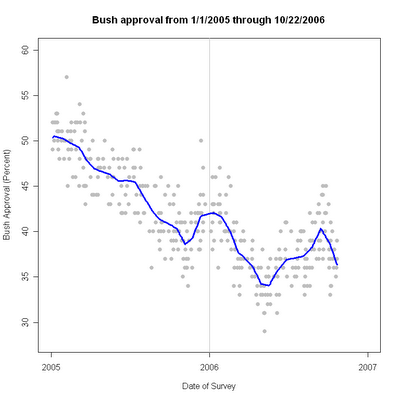

By comparison, approval of President Bush's handling of the Iraq war remained above 50% until September of 2003. During the fall of 2003, approval bounced around in the 45-50% range across various polls. This changed in December 2003 with the capture of Saddam Hussein, when approval rallied again to the 60% range. This again fell, and most of 2004 found approval varying in the 40-50% range, with some improvement to the high 40% range in most polls as the November 2004 election approached. Approval of President Bush's handling of the war has fallen steadily throughout 2005, to current levels in the low 30% range. These approval levels are now approaching the all time lows of the Johnson administration.

In contrast with Presidents Johnson and George W. Bush, President Nixon enjoyed rather strong support for his handling of Vietnam. Despite some general decline in support during his first term, fully three-quarters of the Nixon polls are above 46% approval, and only two polls throughout his term fell below 40% approval. Half of Nixon's polls find approval levels over 52%. Approval improved from a median of 52% in 1969 to 53% in 1970, then fell to a median of 46% in 1971. The all time low reading of approval for Nixon's handling of the war came in April 1971, at 32%. However, as is clear from the graph, that was an unusually low reading (ironically, as that poll was one conducted for President Nixon by Opinion Research Corporation). Average approval was still about 40% at that time. Nixon's approval ratings rebounded strongly throughout 1972 to a median of 54% as the Paris Peace Talks appeared to make progress, and topped out at a median of 65.5% in 1973 with the conclusion of the peace accords.

President George H. W. Bush enjoyed much stronger support for the brief Gulf War of 1991. In the immediate aftermath of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait approval of his handling of “the situation with Iraq and Kuwait” (or words similar to that-- there was some variation across polls.) was very high, peaking at 83% in August 1990 shortly after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. Support for Bush's handling of the situation then declined sharply until November 1990, bottoming out at 50% in a November 15 CBS poll. Subsequently, support increased as the U.S. diplomatic and military preparations for the Gulf War took on renewed urgency. Approval rose to the mid-60% range on the eve of the war, then surged to a high of 88% in a LA Times taken January 18, 1991. Approval remained in the mid-80% range though the end of the war. The last reading, taken April 9, 1991, also by the LA Times, was 80%. (Subsequent polling focused on post-war conditions and retrospective questions of whether military operations should have continued into Iraq and deposed Hussein. I've not mixed those questions in here with approval of handling of the war proper.)

If we can generalize at all from these results, I think it is that Nixon's “Vietnam-ization” strategy, combining negotiations, shifting fighting to Vietnamese troops, reducing U.S. troop commitments, even while maintaining heavy air support and bombing activity, won substantial approval from the public. (As an “approaching draft-age” high school student at the time, I was frankly surprised by these results. I remember a much less popular war which I had assumed had dogged Nixon's approval ratings. As the data show, one person's recollections aren't a very good measure of what the polls actually showed.)

If we assume the current administration is committed to continued troop presence in Iraq for the foreseeable future, the prospects for a recovery of President Bush's approval look bleak, barring a dramatic improvement in the Iraq insurgency situation. A shift to a clear “Iraqi-ization” of the war, in deeds as well as words, might possibly produce approval similar to President Nixon's. Or perhaps that has to wait for a new administration in 2009 to adopt a clear change in policy. The one important difference is that Johnson had only 16 months left in office when his approval ratings reached bottom. President Bush still has over 38 months remaining.

Data: I used all polls from any polling organization that asked questions that directly measured approval of a president's handling of the respective wars. Data are from the Roper Center's iPoll (subscription only) database.

Low Points:

Johnson, 27%, Gallup, 8/29/1967

Nixon, 32%, Opinion Research Corporation, 4/1/1971

GHW Bush, 50%, CBS/NYT, 11/15/1990

HW Bush, 30%, Newsweek/PSRA, 11/11/2005